Sugar…..Not So Sweet For Your Gut And Skin

The Western Diet does not support the demands that come with modern living. In fact, it amplifies naturally occurring metabolic events of inflammation and oxidation throughout our whole body1 with damaging consequences. The increased intake of processed foods encourages the development of hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance, loss in microbiome diversity, and an abnormal activation of the sympathetic nervous system 2,3 which all cause a slow erosion of our mental and physical health. Depending on your genetic susceptibility, these changes ultimately lead to cardiovascular disease, depression, anxiety, obesity, diabetes, respiratory problems, and cancer.

From a young age, these health risks are more evident in people living removed from the natural environment. By contrast, they are virtually absent in hunter-gatherers and other non-westernized populations4. Therefore, with the environmental toll of modern living, we need to be proactive with diet and additional supplementation to improve our resilience.

One of the biggest barriers to our health is the overconsumption of fructose, a widely used sweetener in processed foods. Fructose is a simple sugar naturally occurring in fruits and vegetables and is largely harmless unless you suffer from fructose malabsorption or genetic predisposed fructose intolerance.

However, fructose by itself is widely used as a sweetener and is one of the most dangerous ingredients of the Western Diet. One form is high fructose corn syrup, which has been associated with liver damage, obesity, diabetes and cancer. Studies on Fructose indicate that it damages the gut5 ,weakening the gut barrier 6, the surface that determines how we process incoming information from the outside world. This effect of sugar intake on the skin barrier has equally damaging consequences increasing its fragility and sensitivity to the environment.

Fructose is associated with symptoms of irritable syndrome 7 and SIBO (Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth). According to research published in Nature 8, fructose increases gut permeability leading to intestinal ‘leakiness’ of toxins. into the bloodstream. In the cardiovascular system fructose increases blood pressure, blood vessel stiffness and hyperlipidemia9 and for in our bones and cartilage, fructose makes our bones fragile disrupting collagen structure.10

For the skin, imbalance in sugar metabolism contributes to acne 11 and accelerates the aging process. Here the weakening of collagen causes visible changes including dry skin, fine lines and wrinkle formation as the skin loses its elasticity and ability to retain hydration. 13

The low fiber intake in the Western Diet 14 further influences the effect of sugar on our health with low fruits and vegetables in our diet. Fiber helps to improve gut function and control blood sugar levels. Soluble fiber promotes healthy microbial balance in the gut 15, slows the absorption of sugar and reduces glycation 16. Glycation is a process where the excessive exposure of proteins and lipids to sugar produces Advanced Glycation End Products. AGE’s are damaging to every cell in the body and have been linked to cataracts, Alzheimer’s disease, cardiovascular disease, stroke, asthma, neuropathy, and arthritis including accelerated skin aging.. The benefits of soluble fiber are further enhanced with the presence of polyphenols 17 which encourages the growth of healthful bacteria in the gut and the production of powerful anti-inflammatory and antioxidant metabolites that counter the effects of AGE’s.

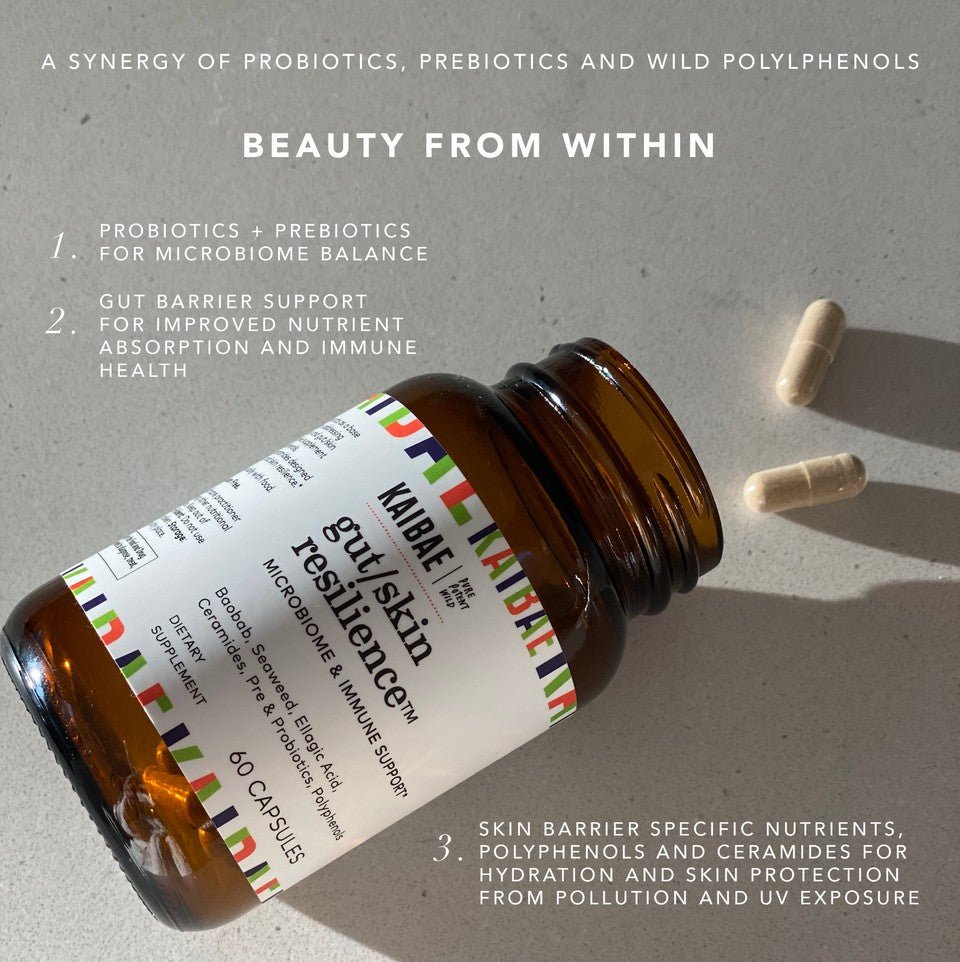

At KAIBAE we emphasize the use of wild plants such those present in Gut /Skin Resilience with Baobab, rich in prebiotic fiber, vitamin C and polyphenols 18 to amplify probiotic balance and fortify gut and skin barrier health. We recommend a whole food19 Mediterranean diet. A diet that is largely composed of plants, wild caught fish and organic fruits and vegetables, while avoiding gluten and high fructose processed foods. These dietary recommendations can further be personalized with your health care provider addressing food sensitivities and allergies.

- Christ A, Lauterbach M, Latz E. Western Diet and the Immune System: An Inflammatory Connection. Immunity. 2019;51(5):794-811. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2019.09.020

- Zinöcker MK, Lindseth IA. The Western Diet-Microbiome-Host Interaction and Its Role in Metabolic Disease. Nutrients. 2018;10(3):365. Published 2018 Mar 17. doi:10.3390/nu10030365

- Thompson SV, Hannon BA, An R, Holscher HD. Effects of isolated soluble fiber supplementation on body weight, glycemia, and insulinemia in adults with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(6):1514-1528

- Tarantino G, Citro V, Finelli C. Hype or Reality: Should Patients with Metabolic Syndrome-related NAFLD be on the Hunter-Gatherer (Paleo) Diet to Decrease Morbidity?. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2015;24(3):359-368 doi:10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.243.

- Melchior C, Douard V, Coëffier M, Gourcerol G. Fructose and irritable bowel syndrome. Nutr Res Rev. 2020;33(2):235-243. doi:10.1017/S095442242000002

- Cho YE, Kim DK, Seo W, Gao B, Yoo SH, Song BJ. Fructose Promotes Leaky Gut, Endotoxemia, and Liver Fibrosis Through Ethanol-Inducible Cytochrome P450-2E1-Mediated Oxidative and Nitrative Stress. Hepatology. 2021;73(6):2180-2195. doi:10.1002/hep.30652

- Melchior C, Gourcerol G, Déchelotte P, Leroi AM, Ducrotté P. Symptomatic fructose malabsorption in irritable bowel syndrome: A prospective study. United European Gastroenterol J. 2014;2(2):131-137. doi:10.1177/2050640614521124.

- Patricia M.Nunes and Dimitrios Anastasiou Fructose in diet expands the surface of the gut and promotes nutrient absorption. Nature,news and reviews 2021 august 18

- Cicero AFG, Fogacci F, Desideri G, et al. Arterial Stiffness, Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Fruits Intake in a Rural Population Sample: Data from the Brisighella Heart Study. Nutrients. 2019;11(11):2674. Published 2019 Nov 5. doi:10.3390/nu11112674

- Tian L, Wang C, Xie Y, Wan S, Zhang K, Yu X. High Fructose and High Fat Exert Different Effects on Changes in Trabecular Bone Microstructure. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22(3):361-370. doi:10.1007/s12603-017-0933-0

- Melnik BC. Linking diet to acne metabolomics, inflammation, and comedogenesis: an update. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:371-388. Published

- Danby FW. Nutrition and aging skin: sugar and glycation. Clin Dermatol.2010;28(4):409-411. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.03.018

- Nguyen HP, Katta R. Sugar Sag: Glycation and the Role of Diet in Aging Skin. Skin Therapy Lett. 2015;20(6):1

- Clemens R, Kranz S, Mobley AR, et al. Filling America's fiber intake gap: summary of a roundtable to probe realistic solutions with a focus on grain-based foods. J Nutr. 2012;142(7):1390S-401S. doi:10.3945/jn.112.160176

- Nakajima A, Sasaki T, Itoh K, et al. A Soluble Fiber Diet Increases Bacteroides fragilis Group Abundance and Immunoglobulin A Production in the Gut. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2020;86(13):e00405-20. Published 2020 Jun 17. doi:10.1128/AEM.00405-20

- .Vlassara H. Advanced glycation in health and disease: role of the modern environment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1043:452-460. doi:10.1196/annals.1333.051

- Khanam A, Ahmad S, Husain A, Rehman S, Farooqui A, Yusuf MA. Glycation and Antioxidants: Hand in the Glove of Antiglycation and Natural Antioxidants. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2020;21(9):899-915. doi:10.2174/1389203721666200210103304

- Coe SA, Clegg M, Armengol M, Ryan L. The polyphenol-rich baobab fruit (Adansonia digitata L.) reduces starch digestion and glycemic response in humans. Nutr Res. 2013;33(11):888-896. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2013.08.002

- Solway J, McBride M, Haq F, Abdul W, Miller R. Diet and Dermatology: The Role of a Whole-food, Plant-based Diet in Preventing and Reversing Skin Aging-A Review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(5):38-43.